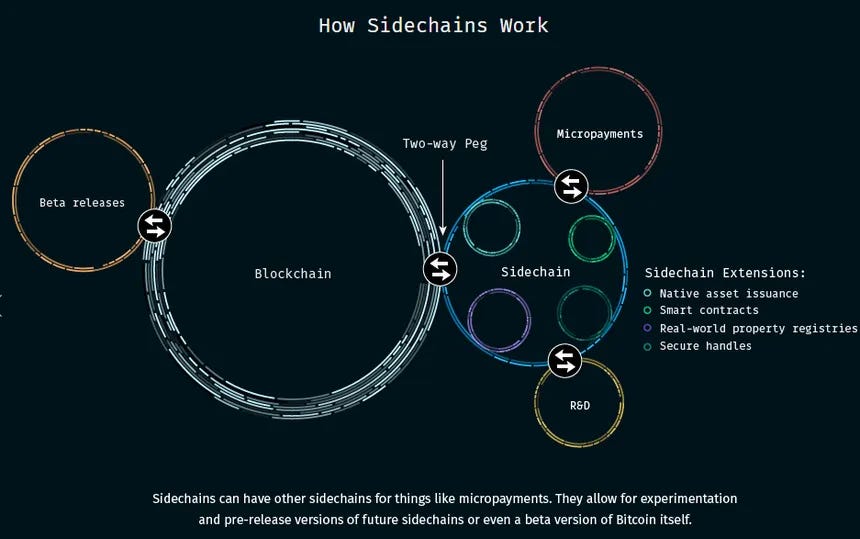

In the before times, circa 2014, the original Blockstream vision (BSV?) was to scale Bitcoin via multiple sidechains, connected by a two-way peg that let Bitcoin move back and forth between chains. In practice, building a bridge like this, while still letting users exit sidechains without trusting a third party turned out to be much harder than expected.

Another narrative was that altcoins like Ethereum and Zcash were merely science experiments, testing ideas that would eventually make their way back to Bitcoin. That prophecy largely failed to materialize.

Until 2023, the year that the only other use case for blockchains – gambling on JPEGs and tokens – returned to Bitcoin in the form of inscriptions and runes. These protocols have made up the majority of Bitcoin transactions over the past few years, while more traditional monetary uses have yet to consistently outbid them for blockspace.

This matters, because blockspace demand is Bitcoin’s long-term security model. ETH maxis have long worried about Bitcoin’s security budget, and what will happen to miners incentives when the block subsidy ends in 114 years. Despite them having no idea what will happen with their chain in the next 3 months, it’s a criticism that merits our careful consideration.

Bitcoin’s blocks are full, but miners fees are low. By 2036 (3 halvings away) the block subsidy alone will be a mere 0.390625 BTC (at today’s prices, $1.7B USD/year seems a touch too light to secure the global economy). It is an open question if the subsidy will be enough to secure Bitcoin, especially if it continues to be seen as just “digital gold”, on-chain activity could be too low to pay our hard-working miners.

Fortunately, there is reason to be optimistic that miner incentives will not be an issue: a new demand for blockspace is coming in the form of rollups, the true inheritor of Blockstream’s promise of a functional 2-way peg..

Rollups

Since 2020, the Ethereum project has been working on a roadmap that focuses on rollups being the primary scaling solution for their chain. Meanwhile, Bitcoin devs have been focused on channel-based scaling (lightning network), sidechains (Liquid, Rootstock), and centralized custodial solutions (eCash, Bitcoin banks). More recently, there has been a resurgence in co-signing protocols (ark/statechains) which allow for more concentrated liquidity than channels, with fewer custodial tradeoffs.

Most Bitcoiners, myself included, lack a clear understanding of rollups, largely because rollups were long considered impossible on Bitcoin. The invention of BitVM changes that, and it’s time we start paying attention.

Rollups combined with BitVM are one proposal for how to scale Bitcoin, with their own tradeoffs. Let’s look at how they work, and what those tradeoffs are. The standards for building on Bitcoin are high. Do these rollup designs live up to those standards?

What makes something an L2?

It’s very simple:

Every user can get their money back on to Layer 1 even if the L2 is malicious, either by playing dead, attempting to steal, or any other misbehavior.

What projects currently meet this requirement?

Does a BitVM rollup meet these two requirements?

Not exactly no… But don’t despair! It’s not far off! In a BitVM rollup you require at least 1 of the bridge operators to be acting rationally and you can withdraw. (If the sequencer lets you, more on that later.)

Rollups, on Bitcoin

A rollup is a blockchain that executes transactions off-chain and submits proofs of state transitions to the underlying blockchain for validation. The rollup commits state diffs (or summaries of the changes made in the last set of off-chain transactions) to the L1. Posting the state diffs to the L1 allows anyone to reconstruct the rollup’s state by applying each batch’s state diff in order from genesis.

Let’s go through the components needed to create a rollup, and then move on to how BitVM, the Turing-complete scripting virtual machine fits in. There are different approaches and designs (Citrea, Alpen), but here we give a general overview.

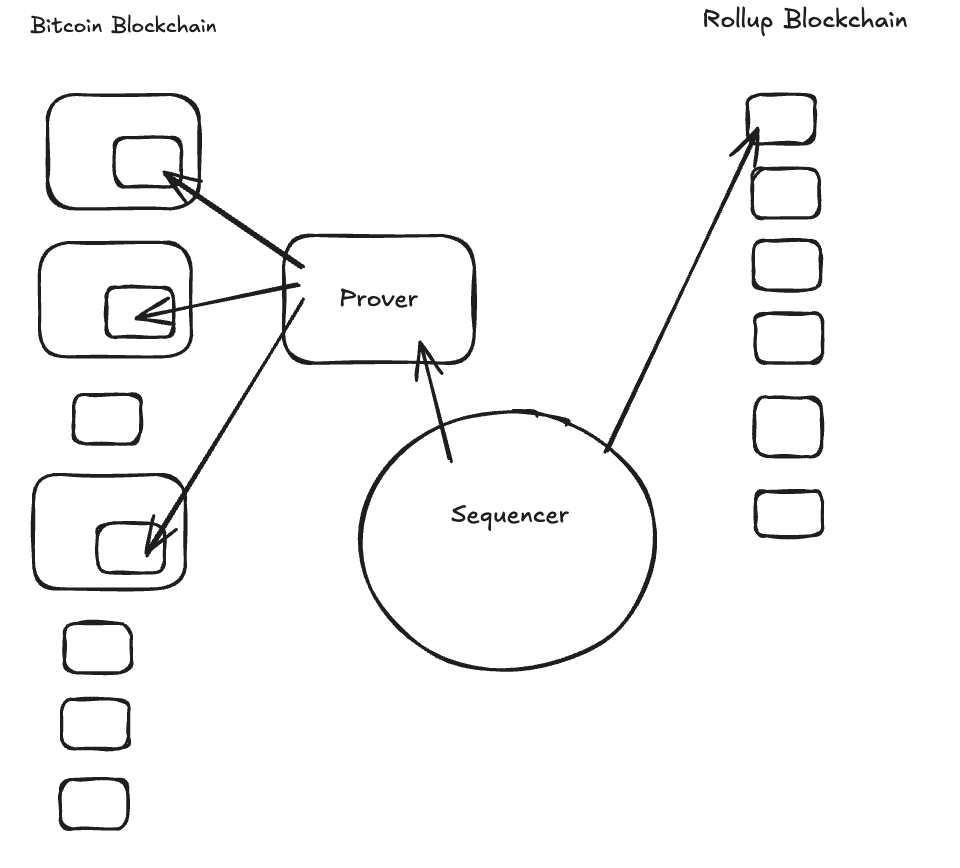

A rollup has several components, the sequencer, the prover, full nodes and a DA or Data Availability layer,. In our case, the Bitcoin blockchain is the Data Availability layer.

The Sequencer

At the heart of every rollup sits the sequencer. The sequencer receives rollup transactions and assembles them into blocks, deciding ordering and inclusion.

You can think of it like a single miner with a private mempool.

The sequencer sets the speed of block generation on the rollup. Blocks are created as quickly as the rollup design decides, and this is configurable. In practice, it’s usually a few seconds (Citrea has 2-second block times).

Bitcoin is slow to make new blocks, and blockspace is scarce, so the sequencer doesn’t post every block on bitcoin L1, it “rolls up” blocks and submits them together. This batch of blocks also includes the state diff and a small piece of data called a proof, which proves the block followed the rules of the rollup.

Some rollups post data on-chain before the proof is ready, to pre-commit to the outcome (Citrea commitment TX). Others post a checkpoint that includes both the commitment to the rollup blocks and the proof that those blocks are valid (Citrea Proof TX). This gives the rollup an L1 anchor for a set of rollup blocks.

The rollup batch size is configurable. It can be triggered after a certain amount of blocks, or earlier if the overall state diff reaches a certain size.

In these designs, rollup blocks are signed by the sequencer and full nodes/provers validate those signatures. Only state diffs/proofs go on Bitcoin; rollup full nodes still fetch rollup blocks from the sequencer or other rollup node peers. However it is entirely possible to sync a rollup full node using the state diffs posted on bitcoin.

The proof is mainly used for light clients and bridge operators to verify that a rollup transaction was included in a rollup block and finalized on to bitcoin.

The Prover

In the Bitcoin network, once a block is mined and sent to full nodes, the nodes verify that the block follows all the Bitcoin rules. Nodes execute every script in every transaction in the block, checking signatures and amounts along the way. This is relatively fast and easy to do.

On the rollup chain, full nodes do the same job. However, to reach a globally agreed upon state that light clients and bridge operators can use to quickly verify transactions, a prover needs to post the proof of the block’s execution on‑chain. Anyone can create the proof, but it requires specialized software and a lot of computation, which can take time. So most systems use a dedicated service (”the prover”) to generate proofs.

To create the proof, the prover takes a rollup commitment from the sequencer, and the blocks in the range of commitments, re‑executing them, and producing a proof that can be posted to the Bitcoin blockchain, typically via an inscription‑style envelope. Once the proof is posted on L1 and sufficiently confirmed by 6 or more blocks, the rollup nodes accept this as a finalized state transition. A Bitcoin transaction reaches 6 confirmations to be considered final; a Rollup proof gets posted to the L1 for the transactions in that batch to be considered final.

The proof used in Citrea and Alpen is a ZK proof, but we won’t get into that here. You can just think of the proof as a way for bridges/light clients to verify the rollup state without replaying everything on a rollup node. Full nodes still re‑execute blocks themselves.

The Fullnode

So it turns out that mastering Ethereum was actually a Bitcoin book after all. Alpen and Citrea both use the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) as the execution environment for their rollup.

Fees on the rollup are paid with bitcoin that’s been bridged to the rollup chain. It acts similar to WBTC (wrapped bitcoin). As the rollup is using the ethereum virtual machine, fees are paid in “gas”, but instead of using ethereum, you use the bridged wrapped bitcoin instead.

Users and wallets send transactions to the sequencer, typically via a full node’s RPC interface. Full nodes poll the sequencer for new blocks, verify them as an Ethereum node would, and update their local state. Block times are determined by the sequencer.

Since all state diffs are committed to Bitcoin alongside proofs, a full node can also sync entirely from the Bitcoin L1: they go through the L1 blockdata to find all of the rollup’s published state diffs, and apply each one, in order, from the rollup’s genesis. The end result should match the current rollup state. No reliance on the sequencer required.

Until a proof is posted and confirmed on L1, blocks are only soft‑confirmed by the sequencer. They’re accepted locally, but until the proof has 6 blocks or so, the state is not considered finalized.

A lot of applications that are running on the rollup will be fine with using the sequencer’s block data directly. For example if your contract was a game, then you can probably trust the sequencer alone, which makes the applications very quick. However, if you were making a large trade on a decentralized exchange contract, then you may want to wait for the block to be included in a proof on the Bitcoin blockchain.

Risk Factors

The prevalence of centralized sequencers is among the biggest safety risks for rollup users. Billions of dollars trust similar centralized setups in the ethereum world; and I’m happy about that for them. It would shock the conscience for Bitcoiners to agree to a similar threat model. So I don’t think they will.

Maybe I am biased. After all, I’m working on the char.network, which is essentially a decentralized sequencer for Bitcoin based rollups. And, most rollups state clearly that moving to a decentralized sequencer is a part of their roadmap.

Some projects, such as Starknet, are already using a decentralized sequencer architecture. For Starknet this means 3 nodes run by 3 operators whose names all seem to begin with Stark and end with Net.

This also affects bridge operation (which we will get into next). The sequencer can always refuse to include the transaction that kicks off your bridge withdrawal. And if that transaction never makes it into a rollup block, there’s no path to getting your bitcoin back to the mainchain.

Ethereum rollups try to mitigate this with “forced transactions“ (a way to bypass the sequencer and still get included). Forced transactions are still an open research problem that Bitcoin rollup projects are working on.

Another point to make is that whoever is privileged enough to run the centralized sequencer, makes a lot of money in transaction fees and MEV. You could say they are incentivised to play honestly, but they can still easily censor transactions and bridged bitcoin withdrawal requests.

One last risk users bear under this rollup architecture is the expense of committing to the state diff and proof data to the L1. Who knows what the blockspace fee market will look like in a few years? It could be incredibly expensive to commit these proofs to the Bitcoin chain. Rollups paying high fees is good problem for Bitcoin itself, but if the rollups are not getting used much, then paying high fees to commit data would not make economic sense, and users would be stuck with a pricey bill to remove their funds.

Sequencers, provers, rollup full nodes, and the EVM explain how the rollup is architected, but how does the “two-way” peg to the L1 work? How do we move bitcoin back and forth between the two systems?

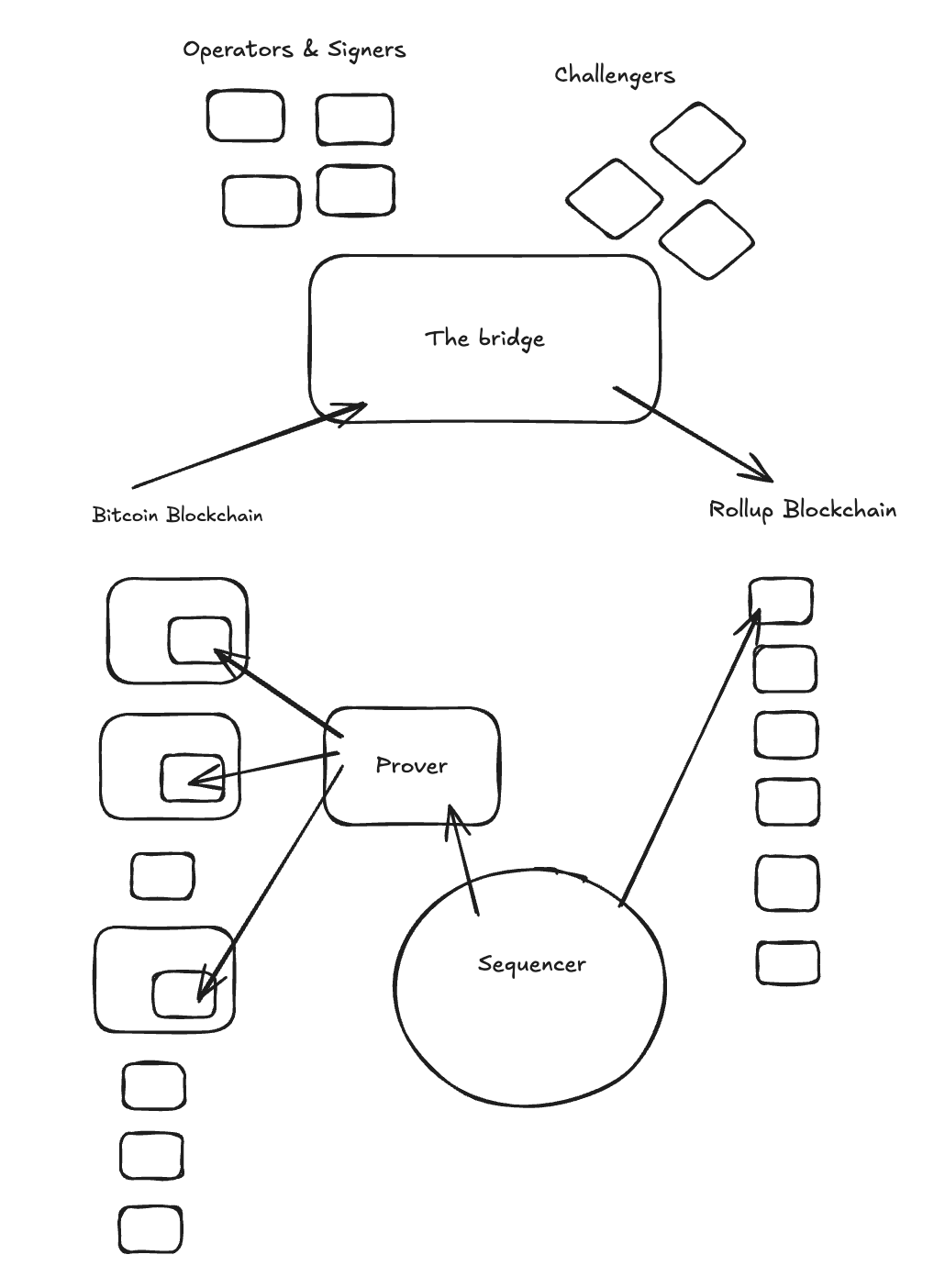

The Bridge

Most Bitcoin bridges that exist today (Liquid, WBTC, etc.) rely on a federated multi-sig, where you need a threshold of signers to allow you to withdraw your bitcoin. We call this a 1-way peg, since you can send your bitcoin into the contract, but need help from enough of the multi-sig signers to get it back out again.

A BitVM-style bridge is also a 1-way peg, but the number of participants needed is different: you only need one active operator who plays by the rules to withdraw your bitcoin. There could be 100 operators in theory, so you can see how this gets interesting – as long as one of these operators is acting rationally, and is still online, you are able to get your bitcoin back to the mainchain. Maybe we can call it a 1.5-way peg.

You also rely on a challenger who can step in and prove fraud if an operator tries to cheat.

In a BitVM bridge, there are operators, signers, and challengers*.

Signers exist to “lock in” the bridge rules during setup. Signers create an emulated covenant by pre-signing the only valid spend paths and then delete their keys. As long as at least one signer is honest and deletes their key, nobody can later create an alternate withdrawal path and send the money anywhere they like.

Operators do the day-to-day work during rollup operation: they watch the rollup, front withdrawals, and later claim reimbursement from the bridge.

Challengers keep operators honest by watching proofs posted to the L1 and challenging bad claims.

*Citrea uses the concept of watchtowers, which is a permissioned set of challengers. We won’t get into that here though.

For simplicity, I’m going to assume the bridge signers and operators are the same group of entities, even though conceptually they’re different roles. The signer role could be removed entirely if Bitcoin had some kind of covenant opcode (ctv btw). Citrea’s bridge does follow a slightly different security model, which allows the signer to be upgraded.

Operators create and manage BitVM instances. They run a SNARK prover off-chain, and use pre-signed Bitcoin transactions (plus a challenge window) to enforce a fraud-proof game around the prover’s output.

Depositing, or Pegging In

For each new deposit, a new BitVM instance is created. A deposit is expected to be around 0.5 to 100 BTC. The average user would most likely enter/exit via atomic swaps / liquidity providers (similar to how Liquid/Lightning get used today), and power users would deposit and withdraw large amounts of bitcoin from the bridge.

First, a user deposits their bitcoin into a staging address. This address allows the bridge operators to sweep the bitcoin into the bridge. If they do not initiate a bridge deposit, the user can withdraw their funds after a timelock.

The bridge operators deposit bitcoin into the bridge by creating an L1 transaction that locks their deposit funds into a BitVM bridge contract, or UTXO, on the L1 Bitcoin chain. The key property of this UTXO is that it’s pre-locked to a specific transaction flow created during setup, assuming at least one signer performed his role honestly, as mentioned previously. In other words, unless 100% of the signers cheated, the BTC can only move along the pre-defined “bridge rules”, which allows the transaction to be challenged if the operators are suspected of breaking the rules.

Once the deposit transaction is confirmed on Bitcoin, users or operators can call a rollup smart contract that emulates a Bitcoin light client, verifies the deposit is included in a Bitcoin block, and mints wrapped BTC to the user’s rollup address.

Withdrawing, or Pegging Out

Withdrawing is simple as long as one operator is active, and there’s at least one party willing to challenge fraud if needed.

Here’s the steps a user would follow to withdraw their bitcoin from the rollup back to the Bitcoin L1.

Burn on rollup - The user burns their wrapped BTC on the rollup (making it unspendable on the rollup).

Operator fronts the Bitcoin withdrawal - The user creates an incomplete Bitcoin withdrawal transaction using an ANYONECANPAY-style sighash so that an operator can attach their own BTC input. Operators compete to front the BTC and publish the completed withdrawal transaction (they do this to earn a fee). One operator wins and the user receives their BTC on Bitcoin.

Operator claims reimbursement from the bridge - This is where the BitVM game begins.

Once the operator has fronted the withdrawal, it broadcasts a claim transaction that pays itself the same amount from the bridge deposits. This starts a challenge period.Operator creates a BTC bond as collateral - Depending on the implementation this is done during the claim process, or when the BitVM instance was created. This bond can be slashed.

Anyone (including other operators, the user, or any third party watching) can verify whether the operator processed the withdrawal correctly, that the rollup burn happened and the corresponding Bitcoin withdrawal is truthful.

If nobody challenges within the window (1-2 weeks), the withdrawal finalizes and the operator gets reimbursed.

If the withdrawal is for less than the original bridged amount, then the remaining bitcoin goes back to the bridge. (The operators will need to make a new BitVM instance for this amount).

If someone challenges and the operator is proven wrong, the operator’s bond is slashed: a portion is sent to an unspendable output (effectively burned via an op_return), and the remainder is paid out as a bounty to whoever posts/completes the disprove transaction (often the challenger).

The BitVM Game

Unlike the EVM rollup chain, the Bitcoin blockchain has no way of verifying a proof directly. This is where BitVM comes into play.

Operators run a prover program (similar to a Bitcoin light client) to which they pass in the following inputs:

A previously known bitcoin block hash

A Bitcoin block hash from after the withdrawal transaction was broadcast

The L1 withdrawal transaction used to front the payout

A rollup proof that was committed to Bitcoin, that proves the wrapped bitcoin was burned on the rollup

The output of the program is a proof that can be used to verify that the operator’s withdrawal was included between the blockhashes and paid out to the user on the Bitcoin L1.

Then the operator posts a reimbursement claim on Bitcoin with this proof.

If nobody challenges during the window, the operator finalizes and gets reimbursed

If challenged, the operator has to commit to more details (Assert TX), and the challenger can force the protocol to check a piece of the verification logic on-chain (Disprove TX); if it fails, then the operator has lied and they get slashed (lose the bitcoin they put into the bond).

With BitVM2, the transactions posted on-chain are very large. The Assert TX is 2 MB, and the disprove TX is 4 MB (close to a full block). However, recent discoveries using Garbled Circuits and Conditional Disclosure of Secrets (see Delbrag, Garbled Locks, BitVM3, BABE, and Argo) should reduce these transactions to only 80 KB of data in total.

What’s next?

Rollups combined with BitVM allow us to create what is very close to the two-way peg that Blockstream envisioned all that time ago. There are still some trade-offs (centralized sequencers, operator assisted withdrawals) that do not quite make them the holy grail of Bitcoin scaling, but new discoveries and breakthroughs are happening all the time.

Citrea launched their BitVM2 rollup this week. Alpen is working on a BitVM3 implementation, and several other teams are building BitVM bridges.

If only a few of these rollups exist and become popular, their demand for blockspace will greatly increase Bitcoin’s security model for the foreseeable future.

Mitigations are being developed to the risks we mentioned earlier. Several teams – including Char Network – are explicitly focused on removing the sequencer trust assumption, which may turn out to be the final step that separates “interesting experiments” from true Bitcoin L2s.

The closer we get to a trustless two-way peg, the closer we are to having private, scalable digital cash. This is an exciting step towards that goal. An EVM rollup is just one example. Once we have a trustless bridge, the possibilities are endless. For example, ZKcoins is a very promising private, client side scaling solution that needs a BitVM-like bridge.

Anyway, I hope this helped explain what these rollups are and how BitVM fits in.

In conclusion, let’s activate drivechains.

Catch stu in person at bitcoin++ exploits edition in Florianopolis next month, talking about “building bridges to north korea” or how chain bridges have historically been exploited. Get a ticket with code INSIDER for 10% off!

Thanks to Niftynei, SuperTestnet, Otaliptus, Ponzini, ecurrencyhodler, Liran, Janusz and Jeremy Rubin for reading drafts of this, and Paul Sportz for the closing sentence.